Friday, September 30, 2011

Final Panorama 1:Central view of Kala Bhavana campus

Its a very memory intensive resourse heavy process, so taking a little longer. But I will upload them one by one.

I learnt how to incorporate the navigation buttons inside the panorama from the software itself after a lot of trial and error.

So for now these dummy buttons.I am going to design new buttons according to my website soon.

For the final panorama shoot I am using a digital SLR camera and a tripod.

Nikon D40

Lens 18-55mm

Tripod:

Simpex

Thursday, September 29, 2011

Artist: K.G.Subramanyam

There are colours all over the world, red and green, blue and violet, sometimes dispersed, often overlapping, meeting each other in a blasé unison – and we see them, here and there, and everywhere. But these colours are not on the things, they are in the eyes that see. There, perhaps, are differences in the eyes of the artists too – as a result of their dissimilar origins, the variety of the societies where they belong, and the difference of values of those societies, the political and economical ambiance, and the customs prevailed. They mark the distinction between the Western and the Oriental, the Aryan and the Tribal, the Courtesan and the Folk. Today, in this 21st century world – in this modern world of elegant dreams with a matte finish, and the clandestine shadows of nightmare hovering over them – when we encounter a piece of art of the present times, often we are confronted with voices from various dialects of arts unified in a harmonic cadence.

Going through a number of traditional forms and pattern, deciphering them to the extent so that a new language might be drawn out from the ancient dialects is a mastery achieved by K. G. Subramanian (born in 1924, Kerala) – blending the Western and the Indian, the folk and the classical to give birth to a concept, innovative and playful, mocking yet soothing is the watermark of his. A chequered life, a graph that goes up and down, covers more dimensions of life than the lineal. From the study in the Presidency College, Madras in Economics, to the imprisonment with a permanent banishment from all academic institution under the British Government, to the admission in Kala Bhavana, Visva Bharati (1944 -1948) and the story to unhindered success from this point onwards – his joining as a lecturer in the M.S University, Baroda (1951), his first exhibition in Delhi (1955) organized by the Shilpi Chakra group, his brief study in the Slade School of Arts (1956), his visit to the New York (1966) and coming back to Kala Bhavana as a professor of painting (1980) –Subramanian’s life seems to be out of the children’s book of fairy tale.

It is, perhaps, the exposure Subramanian accumulated at different phases of his life, from various sources that influenced him in the development of a distinguished language of artistry. However, Shantiniketan, Kala Bhavana, was had always played the most important role in his vision, approach and treatment – the tutelage of Nandalal Bose and the fellowship Ramkinkar Baij, the famed trinity of Kala Bhavana – tradition, nature and freedom impressed him, and he found inspiration by learning various techniques from professional hereditary craftsmen.

As a creative mind, this Professor Emeritus of Visva Bharati, is most versatile. While as a theoretician, Subramanian has dealt with the re – contextualization of the Western theory of art in the Indian aspect addressing the division between craft and art in the Indian traditions, as an artist, he has ventured painting, murals, sculpturing, clay – modelling, toy – making, illustration and designing, as well as terracotta. In his works we encounter a world rich with tradition and the artist’s branching out of it, adding creative richness of the creation itself – the raw directness of Kalighat pots, the elegant courtly female figures, amusing and alluring, the slight hint of irony in its most temperate degree, all congregate to tell an epic wrought in walls, or a terracotta piece, or painted on paper.

edited by Arnab Mazumdar

Artists: Nandalal Bose and Somnath Hore

In the history of Indian art, the first few decades of the previous century played a very vital. Indian art, under the Imperial influence, was getting lost in the pages of history, but in this period a sudden flow of artistic genius injected new life to this mostly dead practice. The success of Ravi Varma and Avanindranath Tagore voiced the existence of artists of international stature in India. Using this as the pedestal, from the third decade of the twentieth century, a number of artists came with new approach and treatment. Interestingly, among these artists, most were the student of Kala Bhavana.

During the foundation of Shantiniketan, Visva Bharati University in 1921, Rabindranath Tagore, the noble laureate poet–dramatist–lyricist–novelist–essayist–artist, had envisaged to form a school of education, altogether different from the conventional British style of education. The open communication between the teacher and the student, the creativity, the close acquaintance with nature – Shantiniketan was characterised by these propensities. It, perhaps, evoked from the horrible personal experience of Tagore as a student that urged him to found a new method of education inspired by the Vedic way of study, known as “Brahmacharya”. Actually, Tagore believed that expression of joy is the result of the abundance of energy in the human self. Hence, in Visva Bharati University he looked into the way to create an atmosphere to recreate this expression of joy. As a poet himself, Tagore understood the topical importance of an arts faculty of exceeding quality to enfranchise the ordeal to weave an ambience capable of nourishing that expression. As a result, Kala Bhavana became the first fine arts faculty in Indian University.

Since then, Kala Bhavana has produced a number of internationally acclaimed artists of the highest quality – from Binodebehari Mukherjee to Ramkinkar Baij to k. G. Subramanian, this journey continued. But when one tries to decipher the secret behind this radical success in visual arts, he finds one single person paving the way for this brilliant originality and talent – that man is no other than Nandalal Bose (born in 1882), the pioneer of modern Indian art.

Bose, a student of the Government Art College (1906), was deeply influenced by Avanindranath Tagore. During his study under Avanindranath and Havell, Bose displayed sparks of his genius more than once. It is because of the immense potential that Avanindranath and Gaganendranath saw within him that they recommended Bose as a professor of arts in Kala Vabhan. In fact, the legend of Kala Vabhan is, chiefly, wrought from the creative and earnest teaching of Nandalal.

But, Nadalal Bose’s acclamation is not merely a result of his success as a teacher of a bunch of artists with worldwide reputation – Bose himself had been the most celebrated creator of Kala Bhavana. The importance of Bose in Indian art is, chiefly, owing to his conscious attempt to deviate from the western style of artistry. While Avanindranath chose to do the same, he went for subjects mythological – shapes out of the lost past or epics. On the other hand, the paintings of Varma were deeply influenced by the courtly British treatment. The connection between art and the commoners was not established. But, despite of the inspiration that Bose found from the murals of Ajanta and the sculptures of Sarnath, he did not choose mythology as his sole subject. In his paintings, for the first time in the modern period, we witness the life of the commoners set against their natural habitat. The rich images of stern, raw nature and the tribal santhal people living in harmony with it, and the influence of the outside world on them served to be Bose’s subjects in many cases. This is clearly evident in his painting “Bagadar Road” (1943, or in “Kinkar’s Statue” (1944) – in both of these paintings, against the background of serene and calm village life, war machines are set in motion in the subtle most manner pointing towards how the waves of the world politics surged to even a village hundreds of miles away from the urban civilization.

In his zeal of reviving the Bengal school of art, Nandalal Bose delved deep into the otherwise unrefined sources of art too. In fact, as Chandi Lahiri, the famous cartoonist, said, the lost art of Kalighat pot was revived by Nandalal in a manner of his own – the sharp contrast of black and white, and the drawing style of the baby of Tagore’s “Sahaj Path” (The Simple Studies), and the unique usage of black at the edge of the painting as if forming a border, bear the essence of this lost art form of Kolkata. In the techniques of his paintings, Nandalal never stopped being versatile.

The oeuvre of Bose’s artistic creations is high in volume – since his early days of a student till the end of his life (1966) Nandalal continued to produce artistic outputs ceaselessly. Apart from the painting, Nandalal also created murals. The famous ‘Black House” of Kala Bhavana is one of the richest example of it. The versatility and deep knowledge of Bose in various forms of art is clearly depicted in this project –from the traditional Indian to the Egyptian and Persian, figures from completely different school of artistry is put together in this mural. In his artistic journey of nearly sixty years, Bose was able to mould the shape of the flow of Indian art. This pioneer of Indian modern art, the doyen of Kala Bhavana was awarded Padma Vibhusan in 1954. Bose’s influence over Indian art is clearly comprehensible from the simple fact that his works are under the National Treasure Act of India.

Somnath Hore

From the moment we open our eyes after sleep, waking up from a world full of shapes and shadows, not prominent, marked by lines, contorted and abrupt, where is no balance of colours, delightful or languid, but mere patches, we move towards the corporeal – towards the high skyscrapers shinning with steely sunlight, towards the streets signed by the tires of the automobiles, red and green, the coffee – shops and waiters with collars prim and modest. We try and imagine the world to be a proper place – a place where everything is fine, and happy, a place lacking suffering and pangs of depression – and, lighting a cigarette, indulge in another dream shaped by the multinational dream – sellers weaving aspirations, tirelessly and with conviction. These dreams that we live wide eyed are luscious, true; as a bioscope of the withered decade, set to our eyes to make us believe the manipulated reality, like a drug the Utopian bliss in our mind, blindfolding the truth. However, Somenath Hore (born in 1921, Chittagong) denied looking into the idiot box. The essence of the muddy air and the crusty earth was more fascinating to him than the Heaven’s Garden.

From Aristotle’s poetics, to the 21st century modern drama the approach of tragedy, going through many winters and springs, shed the age – old apparel of the monarch’s grandeur to become pedestrian, but the intensity remained unchanged. Hore’s drawings and sculptures tell the tale tragedy that our modern world inherits – those suppressions and impoverishment, the death of the budding desires against the thwarting society. They create a reverse panorama, not Utopian, of the real and the ragged. From the early works in the Communist journal “Jannayuddha” to the “Tevaga” series (1946), to the critically acclaimed creations of the “Wound” series of paper – pulp prints (1971) we encounter this other, or perhaps the only, version of reality.

It, perhaps, had been the purpose of Hore’s life to seek for a language suitable to speak out the words of this infinitely suffering, infinitely gentle story of the people living in the darkness of the lamp. From the days of a student of the Government College of Art and Craft, to those of the Indian College of Art & Draughtsmanship as a lecturer this search continued. It is Kala Bhavan, Visva Bharati, that witnesses the attainment of Hore’ enchanting dialect. Shedding the earlier influence of the Chinese Socialist Realism and German Expressionism, or that of the robust style of German printmaker Käthe Kollwitz and Austrian Expressionist Oskar Kokoschka, Hore evolved the style later to be his signature – reducing detailing his individual style of contorted and suffering figures created with a genius use of lines was born.

The later days spent in Shantiniketan, Kala Bhavana as the Departmental Head of the Graphics and Printmaking Department matured the seed of innate talent of Hore – the bucolic trance along with the sweaty figures full of life and dreams, the camaraderie of Ramkinkar baij and K.G Subramaniyam, the characteristic receptivity of the ambience as well as a bunch of students brimming with innovation added to the artistic craftsmanship of the artist fuelling his life – long experiment with form and pattern evident in the etches, intaglios, lithographs, drawings and the sculptures produced during this period (including the “Wound” series, and a number of sculptures among which one of his largest sculptures, “Mother and Child”, a tribute to the people died in Vietnam, was , unfortunately got stolen soon after its completion). Beginning sculpturing since the 70’s, Hore did not fail to develop a language of his own. In fact, the sense of pathos and languidness, the humanity’s inheritance, is, perhaps, even more startlingly manifested in his sculptures – the torn and rugged surfaces, rough planes with slits and holes, exposed channels, subtle modelling and axial shifts – they all added to the integrity of the essence of pure humane tragedy.

Somenath Hore’s journey as an artist expanded in various courses throughout his life in different experimental forms and treatments, all pointing towards to direction of a world beyond the flowery vegetation of the bee and the breeze. Unlike other loud artistic embodiments of despair that hit the mind only to turn it away, Hore’s creations are subtly insidious – going under our skin they disturb us, and make us think – they make us doubt the integrity of the world we see looking into the bioscope sold by the social exploiters. The bones of the unfed ribcages, the stillness of the eyes, the natural tan on the skin, the silenced hunger of the mouth of Hore’s each work are like persistent mosquitoes in the net – they forbid the drugged sleep, leaving us wide awake.

edited by Arnab Mazumdar

Artists: Ramkinkar baij and Binode behari Mukherjee

It feels strange to imagine Ramkinkar Baij in today’s world – every time a student of visual art or perhaps, anyone with a creative mind visits Kala Bhavana he must feels it too. What would have happened if Baij was still alive and assigned with the task to make sculptures in the Airports, or in front the Parliament, or the Reserve Bank of india? It seems fascinating to think that way. Maybe, then we could have encounter another “Mill Call” in the Reserve Bank, or another “Gandhi” in the Parliament – with the congenital intellectual mockery of his, Baij could have created a “Corporate Family” or a “Money Call”. Or, on a second thought, Baij would have refused the offer it flatly. He was a man of passion – commission, fame, reputation, these things meant nothing to an artist that he was. He created for his own satisfaction, to sate the hunger within himself. For everything else, he did not care.

Ramkinkar Baij was among those with a huge potential and absolutely individualistic approach toward the world. In fact, the artistic style and treatment of Baij did not match the typical style of Kala Bhavana at all. Created as an answer to the conventional British method of education, Shantiniketan, Visva Bharati worked as a champion to the ancient Indian style of education in a rather unrestrained manner with a very close acquaintance with nature. Kala Bhavana (the arts faculty of Visva Bharati) on the other hand, focused on the revival of the classical and folk Indian style of art challenging the typical Western artistic format prevailed to that age. But, in Baij, we witness an altogether deviation from the classical format – instead of the painting pattern of Ajanta, or the sculpture pattern if Sarnaath, Ramkinkar goes for a rather western treatment for his oil paintings (as evident in “Lady with Dog” in 1937, or “Birth of Krishna” in 1950), and a unique blend of the folk and the classical for his sculptures (“Buddha” or “Sujata” for example) with his inimitable modern touch.

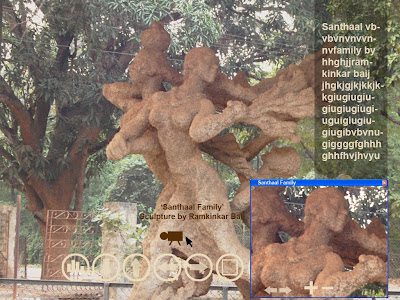

Despite of these dissimilarities of style, Ramkiakr Baij actually could have not been a successful and individualistic artist if he had not joined Kala Bhavana in 1925. It is the unrestricted and open educational system that made it possible to flourish his individuality. His unique style of sculpturing using latarite pebbles and cast cement bears the essence of the tribal santhaal people living in the villages near the premises of Shantiniketan and their lifestyle close to raw natur . Against this backdrop he sets the slight and slow effect of industrialisation and urbanism in motion to depict the history in the most imaginative form – in this he is an artist of the subaltern. “Mill Call” and “Santhaal Family” bear the evidence of this. However, Baij has also dealt with mythological subjects like Nandalal Bose and Binodebehari Mukherjee, his teachers at Kala Bhavana, his treatment was all together different. Again the laterite cast cement forming the lean and slender “Sujata” blending the classical curves of Indian sculpture with the lineal feature of modernism add a new dimension.The view of life of an artist is the interpreter of his artistry. But, as Baij himself said “it is hard to be an artist, but it is harder to understand him”; this statement is, perhaps, is apposite for Baij himself – attending classes in Kala Bhavana, an epitome of celibacy, with a bottle full of native liquor, sleeping on the village road of Shantiniketan with Ghatak after a heavy drink for a whole night, stuffing oil painting on the dripping straw–roof during rain were only possible for him. This embodiment of sheer talent, craziness, an intellectual supremacy and his passion for artistry is peerless.Baij’s fearless observation and statement is at its best in a political work of his. “Gandhi”, created at the time of the Leave India Movement, voices a startling statement while human skulls are shown under the feet of Gandhi. The secret behind this fearless observation of this “Padma Bhushan” winning artist is disclosed by himself in the documentary by Ghatak : While Baij was making a portrait of Tagore, during one sitting, the old poet advised him to approach the subject as a tiger and through the observation suck into its blood. After this, in Baij’s own words, he “did not look back”.

Binode behari Mukherjee

The sun journeys from the eastern sky to the west, and the darkness blankets the world to a tired sleep – twenty four hours pass and then the sun rises again marking another day in her register – book as history. But we remain the same, unaltered. Nothing comes and nothing goes – in this urban world we all are just as Estragon from Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot”. Beyond this urban symmetry of identical boxes, languid and lacklustre, there lies, however, another world where the morning breeze still adores the skin and strokes our hair. Expression, free and charming, lives amid this pastoral domain.

Binodebehari Mukherjee (born in 1904) is a messenger out of that world – a shaper of expressions in the most lucid, yet intense, manner. Nature and the people living with its essence have always found the most vivid and ringing manifestation in Mukherjee’s artistc output.It was the free, unrestrained and culturally rich campus of Shantiniketan, Visva Bharati University – where the stream of life flows in an enchanting unison of the Natural with a tint of modern suppression of urbanism– and the influence of Kala Bhavana’s creative artists of the highest stature regulated and formed the artistic vision of Mukherjee. The congenital curse of the loss of one eye turned out to be a blessing for him – this handicap prevented him to follow a regular educational course and he was admitted to Shantiniketan as a student of the Arts faculty (1919). In Kala Bhavana Binodebehari Mukherjee’s vision found a new dialect. The tutelage of Nandalal Bose and originality of fellow students such as Ramkinkar Baij opened a new vista to him.

While in his early works we encounter a direct influence of Nandalal Bose, as Mukherjee matures as an artist, he successfully forms his own language. After completing his study he joins Kala Bhavana as a teaching stuff. In 1937 Binodebehari visits Japan – the brush stroke style of the 12th century Japanese artists left a deep mark within him. In the fresco on the ceiling of the new dormitory, Mukherjee put an Egyptian fragment of a pond in the middle, but added every detailing that his eyes witnessed from the premises of Shantiniketan – each minute image of the Santhaal settlement nearby, the people, the animals and the nature. His next fresco on the wall of the China Vabhan came two years later. The free flowing treatment of the former had been presented in a more controlled manner in the latter. However, the artistic genius of Mukherjee reaches its peak in the 40’s – apart from countless paintings full of mastery, he created another fresco on the wall of the Hindi Bhavana. Dealing with the life of the medieval saints, this third fresco is a masterpiece of sheer craftsmanship. It is a perfect combination of the traditional Indian concept and expressionist treatment blended with a religious approach that voices humanism. Not the didactic and ascetic doctrine, this bears the essence of the simple philosophy of love and tolerance.

Going through the artistic life of Binodebehari Mukherjee, we notice a sudden turn from 1949. In this year Mukherjee went to Nepal to work as the curator of the Nepal Government Museum, Kathmandu. Moved by the pictorial beauty of a different taste in Nepal, Mukherjee started to capture the native customs, the air and the fleeting aspects of nature. But the deteriorating eyesight soon culminated into the tragedy of the loss of his second eye in 1957.

Visual art and sculpture, in a very basic sense, is the embodiment of a vision, abstract, originated in the artist’s mind, influenced by the scenes that the eyes behold. The loss of eyesight, hence, marks the death of an artist, especially for an expressionist like Mukherjee whose subject always had been the nature and the people. But, this could not blind him – Binodebihari continued his artistic life forming a language altogether different from his previous style. Instead of the descriptive approach to shape and colours, he took resort in the taut simplicity – shedding superfluity of details, Mukherjee went for sketches with aphoristic brevity of mere lines. This journey, from one style to the other, the continuous development of thoughts and ideas, the blending of the rural and the mythological, the expressionism with modernism forms the unique creative language that not only influenced the next generation of artists of Kala Bhavana, but of India, is captured by Oscar winning filmmaker Satyajit Ray in “The Inner Eye”. For his contribution to the Indian art, no doubt, Mukherjee deserved the accolade of Padma Vibhusan by the Govornment of india.

edited by Arnab Mazumdar

Friday, September 9, 2011

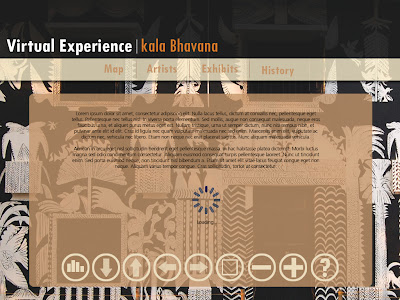

Structure of the website

Homepage might be like this. Contains information about Kala Bhavana on the virtual tour window, navigation buttons on the tour window and the category list with a header.

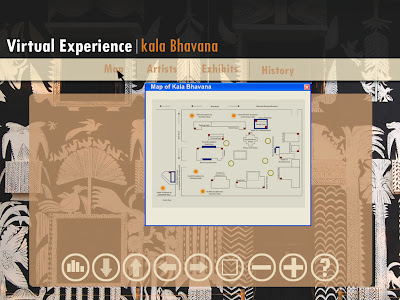

Click on any category and a new window will open up with information. For eg. click on the map button, it will show the physical map of Kala Bhavana in a new window.

Click on the full screen button to see the virtual tour in a full window.

The first panorama of the central space opens up as soon as you click the full screen button. As you can see there are direction buttons given which will take you to the other core areas.

Once you click on a direction button, it takes you to a different core panorama view. Suppose it has taken you to the view of the Santhaal Family sculpture by Ramkinkar Baij, you will get to see a camera (for now) button under the sculpture. Once you click that button, a new window pops in and gives a full detailed view of the sculpture. You can zoom in, out and study the sculpture from different angle. Also information about the sculpture will come scrolling down on the screen.

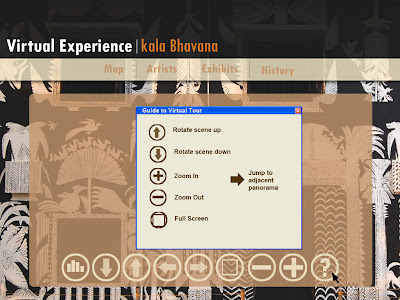

Click on the ? button to get the full information and the guide to the virtual tour and the directions how to use the navigation buttons in a new window.

Navigation buttons for the virtual tour

There would also be some specific direction buttons once you are inside the tour and looking through it. These would help you to change directions in the middle of the tour and visit the different core areas.

Initial layouts for the website

Doing iterations for the Homepage.Figuring out the whole look and feel.What all elements will go up? What all will go in the category list? How will the virtual tour window open? Once it opens what will show first? How will the viewer get to use the navigation buttons for the virtual tour? How will they guide to the virtual tour?

Finally good panoramas happening!

Now with the specialised software, things became easy. With all the photographs taken almost properly, I achieved the below image after the stitch in Hugin. It's still not perfect as one can see. There are a few blurred areas where the control points (points generated and used as references to sync two consecutive images) did not sync properly. And after turning it into the 3D environment, there were a few loopholes. a) The top pole of the image, on the sky, there had been a mismatch in images. In fact the photographs of the sky was yet not complete and so the software stretched the images a bit to make-up for the missing images. b)The top of the attic is a bit curved and distorted. That was bound to happen as there a particular slice of image was missing, and I made it in Photoshop! But overall I was confident that now I can do this.

(Move the mouse pointer inside the image window to move through the image, press shift to zoom, press ctrl to zoom out)

For a full window view go to

http://diplopanarama.99k.org/our%20terrace/DSC_4840%20Panorama4a.html

To eliminate the possibility of getting missing slices in the final panorama, for the next attempt I decided to take a few extra photographs rather than shooting 'just enough' of them. So I decided I will start by taking a single shot of the top pole on the sky, and then I'll tilt down the camera only a little (about 30degree, as the FOV of my camera in full wide angle is around 66degree, and about 50% image overlapping is recommended for a good stitch), and then take a 360 degree rotation to take an overlapping set of a total panorama. Then I'll again tilt down the camera a little, and repeat the process, so on and so forth till I reach the ground. This way I'll be moving in a spiral manner from top to bottom, and will end up practically scanning the whole image dome around me through my camera. Towards the end the tripod would come into the frame, but that too can be masked out in the software.

By this time I was confident enough to go and shoot in the outdoors. So I did in the nearby University ground. And then when I fitted the pieces together in Hugin, voila! It was a perfect 360X180 panorama! The result is given below for all of my readers to see.

For a full window view go to

http://diplopanarama.99k.org/JU%20green%20zone/JU%20green%20zone%20Panorama%20hdr_grain%20reduce_low%20res.html

Next stop: the actual space!

Thursday, September 8, 2011

Image stitching & Image projection

It's a process in which all the images taken for a panorama gets seamlessly stitched together to form a larger photograph, which is extreme wide angle and is projected on a curved surface with the 'observer' inside.

Remember the snow-globe model?

If the photographs taken from standing inside the dome, are combined to make one very large image, and then the image is projected on some similar or almost similar dome shaped curved object, and if the 'observer' is somewhere inside the projection dome, then he will see the same scene seen by the photographer who was on the spot. So this is a convincing process in which it is possible to fool an observers sense of vision, and hence brain to make him believe, that he is standing inside the actual scene! So this is a successful process of achieving virtual reality. You will know what I mean if you have been inside a Pan-hemispheric Cinema, popularly known as 'Space-theaters'. In this cinema the entire huge dome is a cinema screen, and the audience sits inside the dome. If it is a film shot in true pan-hemispheric way, with true fish eye lenses and all the large format film supporting gears, (and not a movie made for I-max format) then when it is projected inside the space-theater dome, it will produce the true perspective correct images, that will give the audience excellent illusion of being at the spot- be it land, up in the sky, or underwater, and even the feeling of movement at times! I-max format films also produce similar effects, but the straight line always gets curved at the edges because of the curvature of the screen.

The Pan-hemispheric cinema

in Kolkata Science City

What goes on inside the pan-hemispheric theater?

So what exactly is image projection? What are the ways to do them?

Image projection is the process of mapping a flat image into a curved surface. This is where I found answer to my first problem (where I forgot to consider the curvature of the dome). The photographs I'm taking are coming as rectangular slices of the scene, but ask a cartographer, he'll know exactly how to put back these flat slices on the curved surface on which I want to rearrange them. On the curved surface, the rectangular slices will no longer be rectangular, in the center they will be slightly curved at the edges, but overall they will be very near to being a rectangle. But at the polar regions, the distortion becomes larger and hence will be more difficult to compensate (see image below). So image projection includes taking all the photographs and projecting them on the correct slices over the globe, and in the process introducing correct amount of distortion on the respective photographs. And image stitching will be the process of stitching these photographs together seamlessly.

My search yielded that there are many softwares out in the market which can efficiently do this job. I tried out two of them. One of them is 'PTGUI Pro' which is very light and extremely efficient. There's another one called 'Hugin' which is free and open source. However Hugin is still under construction and has got some bugs yet to be fixed.

One good thing about these software is that they can automatically read the 'EXIF data' from the camera and correct the photographs accordingly. The Exif data includes the FOV of the photograph and out of that it calculates the barrel distortion of the lens. So my second problem which was the distortion of the lens, is also taken care of now.

I wasted no more time in trying this software out on the same photographs I took from my terrace.

The result was awesome!

Ofcourse this is not an effectively projectable panorama as you can see that many pieces from the sky and ground are missing, so anyways the virtual tour will not be complete, but still one can see how nicely the software stitched the photographs together, blended them, and has introduced the correct amount of distortion into the scene.

Actually this distortion is introduced individually into each of the photographs, and then the distortion in the whole scene is calculated while the stitching goes on. To understand how this distortions takes place, consider the diagram given below.

Now that I found the correct software, I thought of creating a new complete panorama.

Learning by Doing II

Looking at this picture I tried to figure out why the perspective corrections were not achieved by the software I used, to create the virtual 3D environment. (I need to mention here I am using this software called Pano2VR to twist and turn the panoramic image created in Photoshop in the virtual space).

So what did I miss?

What will I have to do to photograph the dome entirely from inside and then stitch photographs properly and gain a panorama that would play perfectly in QTVR or in the flash file?

Looking at the picture it occurred to me in a flash that I was not considering something very important while stitching the photograph. I totally omitted the distortion error created by the curvature of the dome. Its a complex 3D curvature. So the immediate realization that occurs is that there is another distortion factor to be taken care of and that is the barrel distortion created by the camera lens while shooting in extreme wide angle.

For the time being, I was at loss of wit, and tried to correct these distortions randomly through applying distortion and lense correction filters in photoshop. Obviously those didn't help, but there was a fair amount of learning on how the image distortions take place in the virtual 3D space. Here are a few examples:

(Move the mouse pointer inside the image window to move through the image, press shift to zoom, press ctrl to zoom out)

Experiment 1

For a full window view, go to

http://diplopanarama.99k.org/full%20pan%20curved/full%20pan%20curved.html

Experiment 2

For a full window view, go to

http://diplopanarama.99k.org/full%20pan%20sphere/full%20pan%20sphere.html

Experiment 2 distortion is done for a 3D projection option known as 'little sphere'. Here, the whole scene is fitted into a virtual 3D Sphere. The projection told me that the way I tried to fit the scene is wrong, the ground should have been in the middle, instead of the edge.

Experiment 3

For a full window view, go to

http://diplopanarama.99k.org/full%20pan/full%20pan.html

Curvature of the dome, and the distortion from the lens, these two factors when act in combination needs long sets of extremely complicated geometric algorithms to be rectified. Thinking of algorithms it immediately occurred to me that, as these long chain of calculations are beyond normal human brain to perform, so there will have to be some specialized software in order to perform this task. Thus began my quest for the software.

Tuesday, September 6, 2011

Learning by Doing

Our Snow-globe world...

We can understand this process better if we imagine ourselves inside a giant snow-globe. Say, we are standing inside the snow-globe, exactly at the centre, and what do we see when we take a look around? a) the ground we are standing on is like a huge plate,just like the bottom of the snow globe, b) the horizon surrounds us in a huge circle (of course in real life when we are standing on the Earth's surface the radius of this circle, or the horizon, is the distance till which we get clear vision. So this value can change with the movement of the observer). As we start moving up following any line along the horizon, we observe that c) the sky is creating a huge dome over us. Apart from these, all the houses, trees, mountains around us are like 3 dimensional objects scattered along the radius of the plate[see diagram].

So this is what we see, but we do not think of it in this way, because in the back of our head we know that all these are just illusions created by the trickery of perspective. We know that the ground is not a flat plane, and there is always another horizon beyond the one we see at the moment. Interestingly, in ancient times, when people haven't had such scientific notions as perspective, and curvature of the Earth, and people used to gather knowledge through straight observation by naked eyes, they actually used to perceive the Earth just like our model from inside the dome. Limitation of long distance transport actually limited the horizon of their make-belief model of the world till the distance they were able to walk, and because of this, to them Earth was actually like a flat plate!

But though we know the reality, as long as our eyes are convinced, our brain tends to believe in these visuals.

My virtual 3D tour is ready!.....

Unfortunately, as it can be seen from the experiments given below, this brilliant theory didn't work out. So what actually went wrong?

Panorama joined in Photoshop

It seems okay as a flat panorama image. Let's see how it turned out inside the virtual 3D space

(Move the mouse pointer inside the image window to move through the image, press shift to zoom, press ctrl to zoom out, for a full window view, go to

http://diplopanarama.99k.org/negative%20curve/full%20pan%20negative%20curve.html :

So what really went wrong in this Panorama?

1) Pathetic perspective distortion.

2) Enough photos of the sky and the ground were not taken.

3) Edge is not seamlessly attached in the panorama viewing software.

Note: The panorama is viewed here not using the QTVR, but a flash script, embedded with a HTML code. Blogger doesn't directly support QTVR format.